It's not the start of the story, but rather the end, the part I always remember. It reminds me of a big musty bed shared with my little sister in my Grandparent's draughty old house, where we would cower and clasp eachother giggling like fools - half scared, half delighted, as Granny told stories in the dark.

It's not the start of the story, but rather the end, the part I always remember. It reminds me of a big musty bed shared with my little sister in my Grandparent's draughty old house, where we would cower and clasp eachother giggling like fools - half scared, half delighted, as Granny told stories in the dark.____________________________

"This isn't funny Josh, it's getting dark already and I can't get my mobile to work - are you going to be able to get the car started or not..?"

____________________________

Granny would never start her tales in the traditional way, but rather she would start with "When ahh were naught but a girl." and then unfold the story from there. She was awful old my Gran. As wizened as an orange left out in the wind, she'd never admit to an age and yet, for all her claims of aching backs and ricketty knees, she somehow remained as and spry and hearty as a hawthorn bush, all whip and prickle.

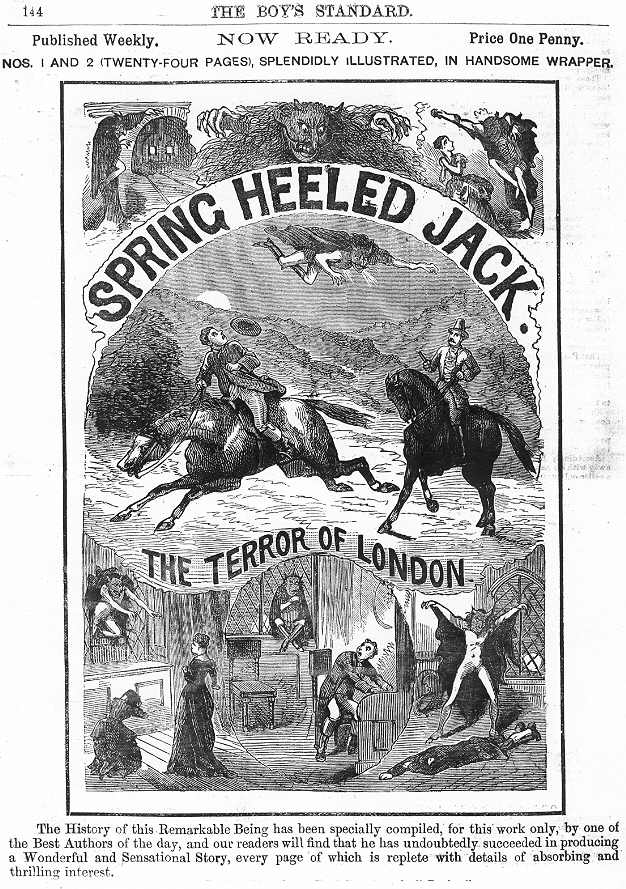

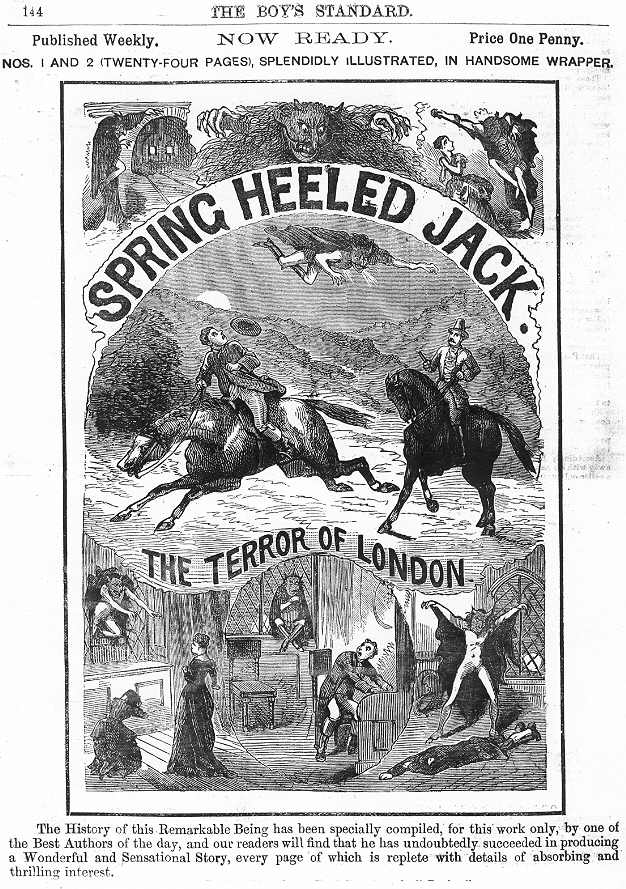

She told us many stories over the years: stories perhaps that parents now would shudder at and not permit - penny-dreadfuls and burlesque - the big bad wolves always got cut in half and those stupid, bone-grinding giants would slit their own stomachs as Jack laughed. River sprites and leering elves and goblins and golems and gollywogs.

And of course Jack.

Jumping Jack.

Spring-heeled Jack.

____________________________

"Ah fuck it - let's just push the damn thing off the road and walk, it can't be more than a couple of miles, I recognise the road. We cross the river soon and then we should be able to see my Gran's old place across the moor. We'll get someone out to the car tomorrow. Better get your boots on though - the snow's thick."

____________________________

Gran lived in Winston: a little village hidden away in Yorkshire, between an old oak forest and high ridge of hills. A river ran through it, cold as Winter and rippled with fish. But Gran hadn't always lived there. In her youth she'd worked as a servant girl in Lavender Hill London and - she would tell us, her eyes far away and suddenly blank - one day as she was crossing the common, a strange figure leapt at her from the dark mouth of an alley. Jack.

"He leapt out t' shaddas at me grinnin' like the very Devil." She'd say and continue to tell of how this fiendish figure had pushed her to the frosted ground and ripped at her dress with his claws which were - and here Granny would loom close over the bed and hook her fingers and we would obediently shriek - "as cold and as clammy as a corpse's". Then she'd "Let out a scream anna whistle loud enought' wake dead" and brought the whole neighborhood running. Jack would escape by half bounding, half flapping across the rooftops "like a bloody great broken-winged bat."

____________________________

After half an hour's slog through the snow and still no bridge I realize two things: that I'm totally out of shape compared to the child that used to run all over the village before breakfast, and that we're lost. Quite seriously lost, considering we're wearing stupid fashion-imitation outdoor gear rather than the real stuff, and now the sun is gone the temperature is falling right off the scale. Beth's breath begins to steam like Granny's old iron kettle. She is silent, all her concentration set on putting her feet one in front of another. The uninterrupted whiteness and the great, overwhelming silence makes it hard to talk somehow, or maybe it's just tiredness, but it still feels like church.

I fall into a dull, leaden rhythm - boots crunching into the pristine crust and out again, breaking a path for my sister behind - and my eyes scan the snow-softened scenary for anything that the child long past remembers from his ramblings. It's cold, every breath is like sucking on ice.

I snort reflexively at how ironic it would be, were we both to die on the way to a funeral.

____________________________

According to popular folklore, little Mary Stevens' story ends with the escape of Jack across the rooftops of old London town, but according to Granny it is actually where her real story begins. Because - as she used to whisper in the warm light of the bedside lamp - when she moved back to her village...

Jack followed.

"The footprints in the snow suddenly ended..."

"The footprints in the snow suddenly ended..."

"That day, my wee ones, the snow were piled up like clouds on the hill-tops and mi breath came out mi mouth like steam from a kettle. Ah were walkin' 'ome cross back field from tarn when ah 'appened upon some tracks. Like normal footprints they were, but not right somehow. An ah knew, knew it right then it were 'im. Summin' crawled right up mi spine an' put up alla the hairs on mi neck straight as wires. 'Cos ye see children, the tracks they just started all at once from nothin' in t' snow. Ah hadda follow 'em too, ah couldn't 'elp it - cos they were 'eddin like an arra right for mi old Mum's 'ouse. This house."

At this point my Sister and I would squeal and gaze horror-struck out of the window, which my Gran would leave unshuttered, the curtains undrawn. And outside the window the snow would roll across the field like a great white ocean: frozen and frosted, crisp and brittle in sharp starlight.

____________________________

"Josh we've been walking for hours - you said it wasn't far - where the fuck are we going..?"

My Sister never swears, and that, coupled with the sheer noise of her voice bursting out of the great cathedral silence all around jerks me out of the trance I've been plodding through for the last couple of miles. I turn, my limbs leaden, suddenly exhausted.

"I'm sorry sweetheart, I think we're in trouble. You wanna try your phone again..?"

Then there is a strange wooshing noise behind me, and an explosion of snow. Beth screams, the noise furious, her breath blasting out like a fire-extiguisher in the luminous dark. I don't want to turn round. I'm seven again, and listening to my Granny's stories. And now as then, I can't help it, my eyes drag my head around, until I'm looking at it. Looking at him. Looking at Jack.

____________________________

And Gran would point out of the window with one shaking hand, gaze into our terrified little eyes and continue: "An when ah got t' 'ouse, e'en though it were colder than a witch's tit that day, ah were sweatin' like a shire'orse. And them footprints - well they got within a couple o' yards o' this very window and just stopped - just ended - like e'd jus' disappeared. An' near where they ended there were a tile come down offen the roof, stuck up in the snow like a teeny-tiny tombstone."

____________________________

Up close it looked nothing like the pictures in Gran's book. Just like she'd said. Blackness slid over it despite the starlight reflecting off the snow all around. It towered over us by a meter or more. Its head dark and featureless save for a banked-coal glimmer of eyes. No arms but more fins, or stunted wings perhaps, jutting out from a torso much too short for its height. It jigged gently on its legs, up and down, never still. It stank, even in the clean frosted air - a noxious smell, like stagnant swimming pools brimming with chlorine and rotten weed. One minute maybe, maybe two we watched it, watched it not breathing even as our own breath tumbled out of us like waves of fog in the icy air.

Quick as a knife it moved, a pale hard pincer grazing my cheek, hard enough to bruise but not hard enough to cut, and then it was gone - squatting down - its legs bending impossibly backward like a giant cricket's - and then whoosing, soaring, vanishing upwards with a sucking vaccuum that plucked at our frosted clothes.

____________________________

Then Gran would sit back and breathe and smile to show us the worst was over. "Well ah got inside the door and slammed it shut behind just as quick as a bird, an tied downt' latch wi' mi best knots ah kin tell ye. Fer a while ah just stood there and caught mi breath, then ah went t' find mi Mum."

____________________________

Spring-Heeled Jack streaked down again like a comet not fifty yards from where we stood, throwing up a great fantail of snow with the force of his landing. Then in a curious series of hopping bounds he began to move away over the moor at a diagonal to the path we'd been making. Every now and again he'd pause, and twist his head around in our direction.

Children again, brother and sister holding hands in the darkness, terrified, we followed.

____________________________

"- Ah found 'er in the kitchen proddin' at' fire. She turned 'roun and gimme such a clip roun' the eer as ye wouldn't wish on ye worst enemy. Then she told me not ta shove anymore snow downt' chimney. 'It's Jack' ah told 'er mi eyes bright wi tears, 'Spring-Heeled Jack's jumped up on our roof' ah said, 'e was the one that done it Mum, not me."

____________________________

There were lights in the darkness ahead, electric and warm. Our limbs suddenly full of energy, we rushed over the snow toward them, trampling through and over the marks of Jack's passing

There were lights in the darkness ahead, electric and warm. Our limbs suddenly full of energy, we rushed over the snow toward them, trampling through and over the marks of Jack's passing

without thought. And then we were at the window, and the footprints suddenly ended.

____________________________

"'No such thing as Spring-Heeled Jack my little lass' mi Mum said, wipin' away mi tears, but ahh knew it alla same, Jack was on the roof- lookin' out fer me." Then Gran would close the curtains and fuss with the blankets, tucking us in snug as mice in a sack. She would stroke our brows and soothe our fretful faces, cooing nonsense words and lullabies until we slept.

...Continued...

"Ah fuck it - let's just push the damn thing off the road and walk, it can't be more than a couple of miles, I recognise the road. We cross the river soon and then we should be able to see my Gran's old place across the moor. We'll get someone out to the car tomorrow. Better get your boots on though - the snow's thick."

____________________________

Gran lived in Winston: a little village hidden away in Yorkshire, between an old oak forest and high ridge of hills. A river ran through it, cold as Winter and rippled with fish. But Gran hadn't always lived there. In her youth she'd worked as a servant girl in Lavender Hill London and - she would tell us, her eyes far away and suddenly blank - one day as she was crossing the common, a strange figure leapt at her from the dark mouth of an alley. Jack.

"He leapt out t' shaddas at me grinnin' like the very Devil." She'd say and continue to tell of how this fiendish figure had pushed her to the frosted ground and ripped at her dress with his claws which were - and here Granny would loom close over the bed and hook her fingers and we would obediently shriek - "as cold and as clammy as a corpse's". Then she'd "Let out a scream anna whistle loud enought' wake dead" and brought the whole neighborhood running. Jack would escape by half bounding, half flapping across the rooftops "like a bloody great broken-winged bat."

____________________________

After half an hour's slog through the snow and still no bridge I realize two things: that I'm totally out of shape compared to the child that used to run all over the village before breakfast, and that we're lost. Quite seriously lost, considering we're wearing stupid fashion-imitation outdoor gear rather than the real stuff, and now the sun is gone the temperature is falling right off the scale. Beth's breath begins to steam like Granny's old iron kettle. She is silent, all her concentration set on putting her feet one in front of another. The uninterrupted whiteness and the great, overwhelming silence makes it hard to talk somehow, or maybe it's just tiredness, but it still feels like church.

I fall into a dull, leaden rhythm - boots crunching into the pristine crust and out again, breaking a path for my sister behind - and my eyes scan the snow-softened scenary for anything that the child long past remembers from his ramblings. It's cold, every breath is like sucking on ice.

I snort reflexively at how ironic it would be, were we both to die on the way to a funeral.

____________________________

According to popular folklore, little Mary Stevens' story ends with the escape of Jack across the rooftops of old London town, but according to Granny it is actually where her real story begins. Because - as she used to whisper in the warm light of the bedside lamp - when she moved back to her village...

Jack followed.

"The footprints in the snow suddenly ended..."

"The footprints in the snow suddenly ended...""That day, my wee ones, the snow were piled up like clouds on the hill-tops and mi breath came out mi mouth like steam from a kettle. Ah were walkin' 'ome cross back field from tarn when ah 'appened upon some tracks. Like normal footprints they were, but not right somehow. An ah knew, knew it right then it were 'im. Summin' crawled right up mi spine an' put up alla the hairs on mi neck straight as wires. 'Cos ye see children, the tracks they just started all at once from nothin' in t' snow. Ah hadda follow 'em too, ah couldn't 'elp it - cos they were 'eddin like an arra right for mi old Mum's 'ouse. This house."

At this point my Sister and I would squeal and gaze horror-struck out of the window, which my Gran would leave unshuttered, the curtains undrawn. And outside the window the snow would roll across the field like a great white ocean: frozen and frosted, crisp and brittle in sharp starlight.

____________________________

"Josh we've been walking for hours - you said it wasn't far - where the fuck are we going..?"

My Sister never swears, and that, coupled with the sheer noise of her voice bursting out of the great cathedral silence all around jerks me out of the trance I've been plodding through for the last couple of miles. I turn, my limbs leaden, suddenly exhausted.

"I'm sorry sweetheart, I think we're in trouble. You wanna try your phone again..?"

Then there is a strange wooshing noise behind me, and an explosion of snow. Beth screams, the noise furious, her breath blasting out like a fire-extiguisher in the luminous dark. I don't want to turn round. I'm seven again, and listening to my Granny's stories. And now as then, I can't help it, my eyes drag my head around, until I'm looking at it. Looking at him. Looking at Jack.

____________________________

And Gran would point out of the window with one shaking hand, gaze into our terrified little eyes and continue: "An when ah got t' 'ouse, e'en though it were colder than a witch's tit that day, ah were sweatin' like a shire'orse. And them footprints - well they got within a couple o' yards o' this very window and just stopped - just ended - like e'd jus' disappeared. An' near where they ended there were a tile come down offen the roof, stuck up in the snow like a teeny-tiny tombstone."

____________________________

Up close it looked nothing like the pictures in Gran's book. Just like she'd said. Blackness slid over it despite the starlight reflecting off the snow all around. It towered over us by a meter or more. Its head dark and featureless save for a banked-coal glimmer of eyes. No arms but more fins, or stunted wings perhaps, jutting out from a torso much too short for its height. It jigged gently on its legs, up and down, never still. It stank, even in the clean frosted air - a noxious smell, like stagnant swimming pools brimming with chlorine and rotten weed. One minute maybe, maybe two we watched it, watched it not breathing even as our own breath tumbled out of us like waves of fog in the icy air.

Quick as a knife it moved, a pale hard pincer grazing my cheek, hard enough to bruise but not hard enough to cut, and then it was gone - squatting down - its legs bending impossibly backward like a giant cricket's - and then whoosing, soaring, vanishing upwards with a sucking vaccuum that plucked at our frosted clothes.

____________________________

Then Gran would sit back and breathe and smile to show us the worst was over. "Well ah got inside the door and slammed it shut behind just as quick as a bird, an tied downt' latch wi' mi best knots ah kin tell ye. Fer a while ah just stood there and caught mi breath, then ah went t' find mi Mum."

____________________________

Spring-Heeled Jack streaked down again like a comet not fifty yards from where we stood, throwing up a great fantail of snow with the force of his landing. Then in a curious series of hopping bounds he began to move away over the moor at a diagonal to the path we'd been making. Every now and again he'd pause, and twist his head around in our direction.

Children again, brother and sister holding hands in the darkness, terrified, we followed.

____________________________

"- Ah found 'er in the kitchen proddin' at' fire. She turned 'roun and gimme such a clip roun' the eer as ye wouldn't wish on ye worst enemy. Then she told me not ta shove anymore snow downt' chimney. 'It's Jack' ah told 'er mi eyes bright wi tears, 'Spring-Heeled Jack's jumped up on our roof' ah said, 'e was the one that done it Mum, not me."

____________________________

There were lights in the darkness ahead, electric and warm. Our limbs suddenly full of energy, we rushed over the snow toward them, trampling through and over the marks of Jack's passing

There were lights in the darkness ahead, electric and warm. Our limbs suddenly full of energy, we rushed over the snow toward them, trampling through and over the marks of Jack's passingwithout thought. And then we were at the window, and the footprints suddenly ended.

____________________________

"'No such thing as Spring-Heeled Jack my little lass' mi Mum said, wipin' away mi tears, but ahh knew it alla same, Jack was on the roof- lookin' out fer me." Then Gran would close the curtains and fuss with the blankets, tucking us in snug as mice in a sack. She would stroke our brows and soothe our fretful faces, cooing nonsense words and lullabies until we slept.

No comments:

Post a Comment